Split Attachment: When Neither Staying Brings Calm, Nor Leaving

Problem description:

“I’m so tired, so unsettled. I’m extremely attached to someone I love deeply. It’s about everything that’s been and is in my mind. But I’m suffering a lot, I feel bad. If I stay, I have to endure constant pain; if I leave, I’m tormented by their absence.”

Analysis Using Unconscious Symbolic Processing Theory (USPT):

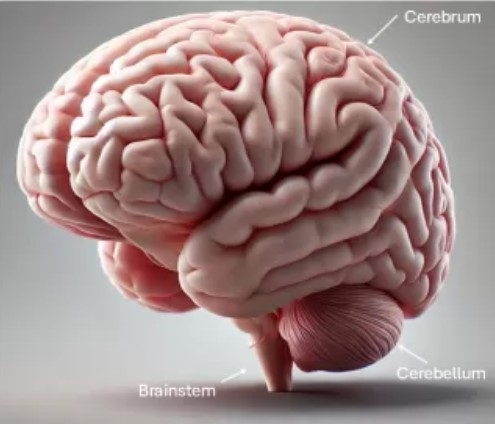

This statement signals a complex psychological state in which the mind becomes entangled between the need for survival and the need for release. What appears on the surface is not just “attachment” or “dependency,” but a far more intricate structure—an overlap of belonging, meaning, and self-image that is intensely conflicted.

Here, the individual is not only attached to another person, but that person seems to represent a “meaningful internal image” within the mind. This image arises from an inner need for belonging, security, and a projection of unrealized desires. The presence of the other acts not only as an emotional companion but as a “source of affirmation and meaning.” Thus, the bond formed is not merely an ordinary relationship; it becomes deeply ingrained in one’s identity and psychological foundations.

The complexity, however, lies in the fact that this source of meaning is simultaneously a source of emotional exhaustion and psychological pressure. To be with this person means enduring constant pain; to be without them means a loss of meaning and a feeling of inner emptiness. The mind faces a structural contradiction: remaining equals ongoing pain; leaving equals cutting off a part of oneself.

At this point, a profound phenomenon occurs—what in USPT is termed “the central executive core conflict.” The “central core” here refers to the inward part of the mind responsible for decision-making, direction, and meaning-making. When the source of meaning and the source of pain become identical within the psyche, this executive center falls into persistent decision-making paralysis. The individual cannot separate because separation equates to the destruction of a central pole of meaning, but cannot stay because staying leads to ongoing depletion.

Under such circumstances, any decision—whether to stay or to leave—brings feelings of loss or emptiness. The mind, lacking some external cleansing mechanism or cognitive reframing, repeatedly circles back into a closed loop. It is not so much that the system is disabled, but rather that it suffers from a critical disturbance in emotional and cognitive prioritization.

Analytical Conclusion:

The situation described here is a clear example of the overlap between emotion and the structure of meaning in the mind; a place where the individual confronts not just attachment, but a threat to psychological cohesion. In such cases, the solution does not lie in hasty decision-making or efforts to forget, but in gradually activating the mind’s capacity to redefine the source of meaning.

In other words, one must be able to transform the meaning of the beloved person from the “core of psychological entirety” to “one important but separable component.” This process is time-consuming and requires inner cleansing and deep dialogue with oneself or a neutral, knowledgeable observer (such as a therapist or even consistent self-analytical writing).

Effective intervention in this state happens when the mind learns to identify the source of conflict, and—by deactivating it at the central decision-making level—relocates its influence to a non-determinative place. This is the starting point for psychological reconstruction, restoring agency, and finding a way to live without seeking meaning solely in the presence of another person.